What Is the LCL?

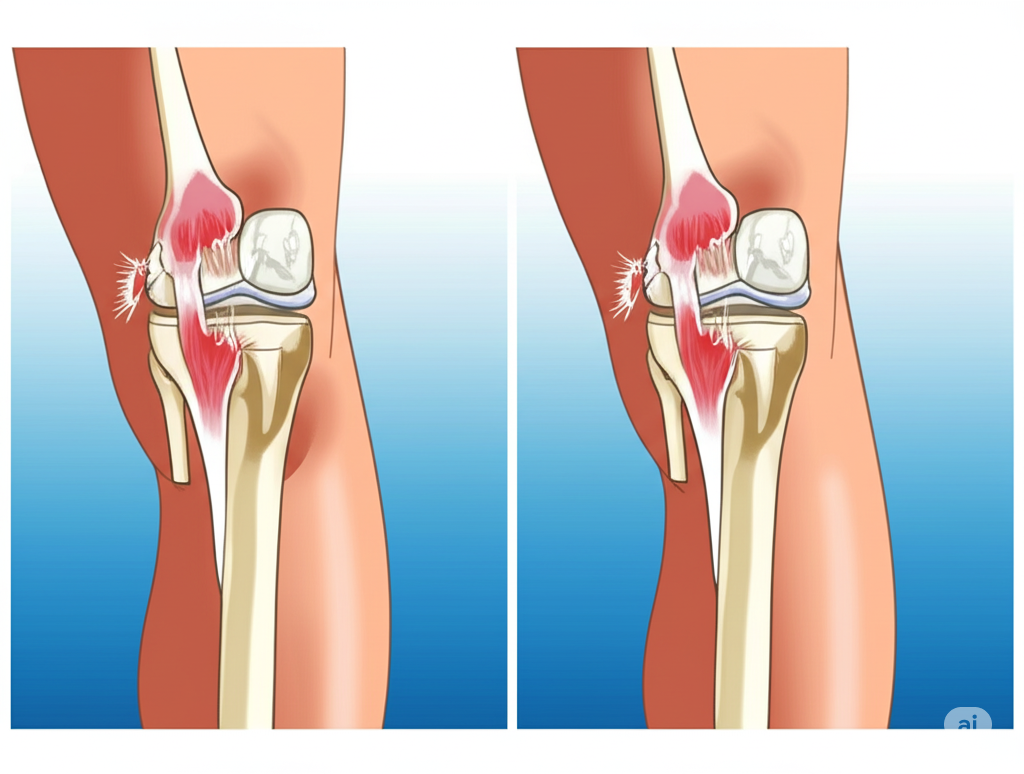

The Lateral Collateral Ligament (LCL) is one of the four major stabilizing ligaments of the knee. It runs along the outer (lateral) side of the knee, connecting the femur (thigh bone) to the fibula (the smaller bone in the lower leg). The LCL works in conjunction with other structures in the outer knee—collectively known as the posterolateral corner (PLC)—to stabilize the joint during side-to-side and rotational movements.

These structures resist varus stress (inward pressure that pushes the knee outward), protect against excessive rotation, and contribute to joint control during high-demand activities like cutting, pivoting, and downhill motion.

What Is the Posterolateral Corner (PLC)?

The posterolateral corner refers to a complex network of ligaments, tendons, and muscle attachments at the back and outer side of the knee. This includes:

-

Lateral Collateral Ligament (LCL)

-

Popliteus tendon

-

Popliteofibular ligament

-

Iliotibial band

-

Biceps femoris tendon insertion

Together, these structures maintain the rotational and varus integrity of the knee. Injury to the PLC is often overlooked but can result in chronic instability if not diagnosed and treated appropriately.

How Do LCL and PLC Injuries Occur?

These injuries typically result from high-energy trauma or awkward twisting motions. Common causes include:

-

A blow to the inner knee, forcing it outward

-

Sports collisions or falls (e.g., football, skiing, wrestling)

-

Traumatic knee dislocations

-

Motor vehicle accidents

LCL and PLC injuries often occur in combination with damage to the ACL or PCL, especially in complex multi-ligament knee injuries.

Symptoms of LCL or PLC Injury

Because symptoms can be subtle at first, these injuries are sometimes missed. Common signs include:

-

Pain or tenderness along the outside of the knee

-

Swelling or bruising over the lateral joint line

-

A feeling of instability or “giving way,” especially during pivoting

-

Difficulty with downhill walking or turning

-

Noticeable looseness or abnormal movement during physical exam

-

In chronic cases: a visible bowing of the knee during walking (varus thrust)

Diagnosis at Kerlan Jobe Institute

Accurate diagnosis of LCL and PLC injuries is crucial for a successful outcome. Our specialists perform a thorough evaluation that includes:

-

Varus stress testing to detect ligament laxity

-

Dial test to assess for rotational instability at different angles

-

Gait observation for signs of varus thrust

-

MRI scans to identify ligament tears and soft tissue damage

-

Stress X-rays to objectively measure joint instability

-

In trauma cases: vascular assessment to rule out injury to nearby arteries or nerves

Due to the complexity of PLC anatomy, these injuries are best evaluated by a surgeon experienced in complex knee reconstructions.

Grading LCL Injuries

Like other ligament injuries, LCL tears are graded by severity:

-

Grade 1: Mild sprain with minimal fiber damage

-

Grade 2: Partial tear with some joint laxity

-

Grade 3: Complete rupture with significant instability, often involving the PLC

Treatment Options

Non-Surgical Treatment

Mild (Grade 1) and some moderate (Grade 2) LCL injuries can often be managed conservatively:

-

Activity modification

-

Bracing to protect the lateral knee

-

Physical therapy for strength and joint control

-

Crutches during early stages (if needed)

Careful follow-up is required to ensure healing and to detect any hidden PLC involvement.

Surgical Treatment

Surgery is typically recommended for:

-

Grade 3 LCL tears

-

Any injury involving the posterolateral corner

-

Cases with combined ligament damage (ACL, PCL, etc.)

-

Chronic instability or failed conservative care

At Kerlan Jobe Institute, surgical repair or reconstruction involves:

-

Reattachment of torn structures if acute

-

Use of graft tissue (autograft or allograft) to reconstruct LCL/PLC anatomy in chronic cases

-

Simultaneous reconstruction of other injured ligaments as needed

Our surgical approach is individualized, anatomically precise, and backed by extensive experience in multi-ligament knee repair.

Recovery After LCL or PLC Surgery

Due to the complexity of these injuries, recovery is more gradual than for isolated ligament repairs. Typical phases include:

-

First 6–8 weeks: Limited weight-bearing, protective bracing, and gradual range of motion

-

Weeks 8–16: Progressive strengthening, gait retraining, and neuromuscular control

-

Months 4–9: Functional rehab, agility training, and return-to-sport preparation

Full recovery for athletic return often takes 9–12 months, especially if combined injuries are involved.

Why Early, Expert Treatment Matters

LCL and PLC injuries are frequently underdiagnosed, and delayed or inadequate treatment can result in long-term knee instability, abnormal gait, and early-onset arthritis. At Kerlan Jobe Institute, we provide:

-

Expertise in posterolateral corner reconstruction

-

Access to advanced imaging and diagnostic tools

-

A team-based, patient-centered approach to rehab and recovery

Our specialists are among the most experienced in the country at managing these rare but complex knee injuries.