Understanding Knee Anatomy

The knee is one of the most powerful and intricate joints in the human body. It supports your weight, absorbs shock, and enables a wide range of motion. Whether you’re a professional athlete or just climbing stairs, your knees are constantly at work.

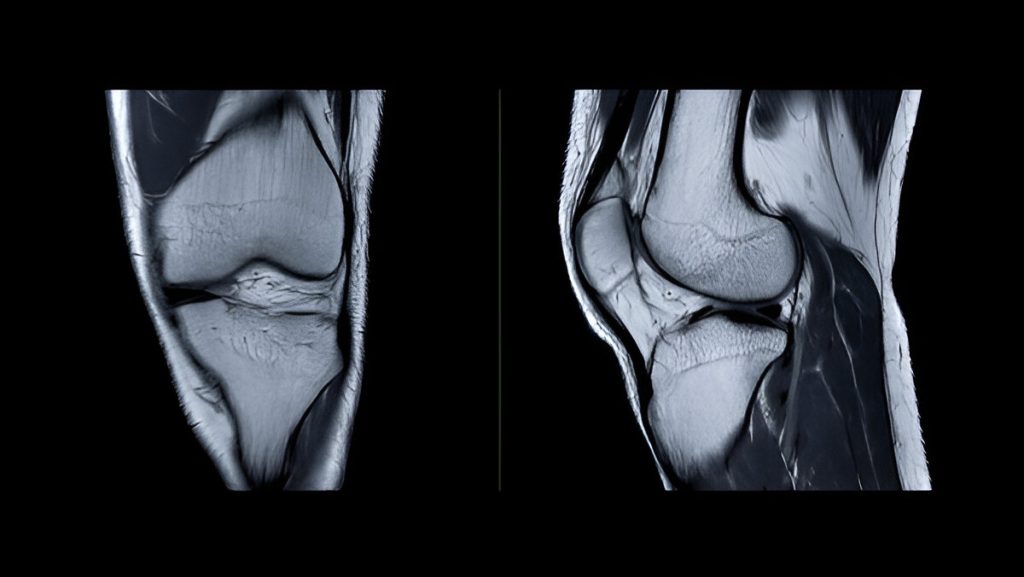

The Bones of the Knee

Femur (thighbone) – Connects the hip to the knee.

Tibia (shinbone) – Supports the body’s weight below the knee.

Patella (kneecap) – Protects the front of the knee and improves muscle efficiency.

These bones articulate at the tibiofemoral and patellofemoral joints.

Ligaments: The Knee’s Stabilizers

The knee is stabilized by four key ligaments:

ACL (Anterior Cruciate Ligament) – Controls rotation and forward motion of the tibia.

PCL (Posterior Cruciate Ligament) – Controls backward motion of the tibia.

MCL (Medial Collateral Ligament) – Stabilizes the inner knee.

LCL (Lateral Collateral Ligament) – Stabilizes the outer knee.

Cartilage: The Knee’s Cushion

Two types of cartilage provide support and shock absorption:

Articular cartilage – Smooth tissue covering bone ends to reduce friction.

Meniscus (Medial & Lateral) – C-shaped fibrocartilage acting as shock absorbers and stabilizers.

Muscles and Tendons: Power and Control

Major muscle groups driving knee movement include:

Quadriceps – Straighten the knee.

Hamstrings – Bend the knee.

Gastrocnemius & Soleus – Support motion from the calf.

Patellar Tendon – Connects the quadriceps to the tibia through the kneecap.

Synovial Membrane and Bursae

The synovial membrane lines the joint and produces synovial fluid for lubrication.

Bursae are small fluid-filled sacs that prevent friction between bones, tendons, and skin.

Why It Matters

Knowledge of knee anatomy helps:

Diagnose and treat injuries like ACL tears, meniscus damage, and arthritis

Design better rehab and performance plans

Prevent long-term damage through early intervention